Doing the Steps: Edward Gorey and the Dance of Art

Perhaps to really understand the work of Edward Gorey one would have had to sit through about 30 years of dance at the New York City Ballet—from approximately 1953 to 1983 (with shaving a few years off at each end—let’d say 25 years, give or take a few years). Gorey once said that he could visualize that progression of ballets in his head, like a movie he could play forward or backward, decades of form and movement and story—literally, at his fingertips.

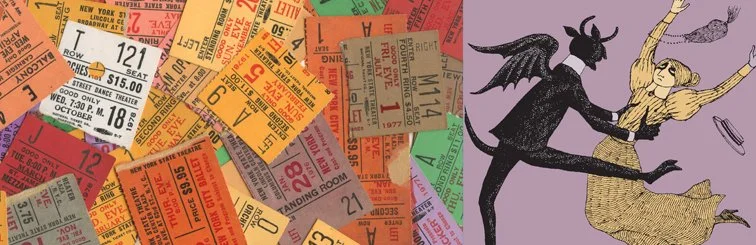

Edward Gorey’s infatuation with the NYCB was centered on the choreography of George Balanchine, whose corps de ballet performed his works like a finely tuned instrument. Whether Gorey actually attended every performance of the NYCB between 1953 and 1983 is, to be honest, open to some conjecture. His friend Robert Greskovic maintains that Edward averaged 160 shows a year—not including all the Nutcrackers. While there is rumor that some ticket stubs were thrown away shortly after his death, those remaining here at the House attest to hundreds of performances some years, less on other years—but certainly not every performance. Whether these tickets represent all, or half, or a mere third of Edward’s actual attendances, they nonetheless reveal a profound devotion to a company and its choreographer.

“Just do the steps” is probably Balanchine’s most famous remark (to his dancers),” Gorey wrote in a 1993 article for Ballet Review. He continued: “Properly considered, it somehow explains everything, and can be applied to whatever you can think of in both art and life.” Gorey consistently cited George Balanchine as his greatest inspiration and muse. It was not a collaborative relationship— Balanchine staged ballets and Gorey simply attended them. The dance viewed nightly during those peak years from the late 50s to the late 70s—masterworks of American Ballet that evolved with every performance and over numerous seasons—became a great reservoir of inspiration for Edward. Whether Gorey appropriated Balanchine’s process or simply recognized the process— we can’t say. We can only present some of what he has put to paper.

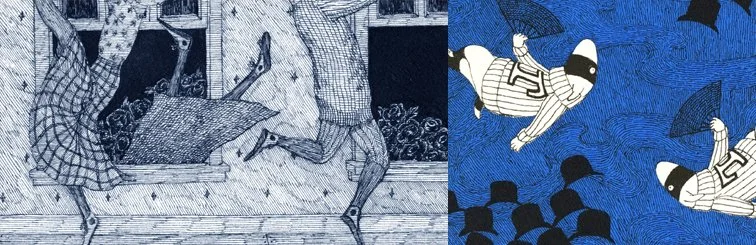

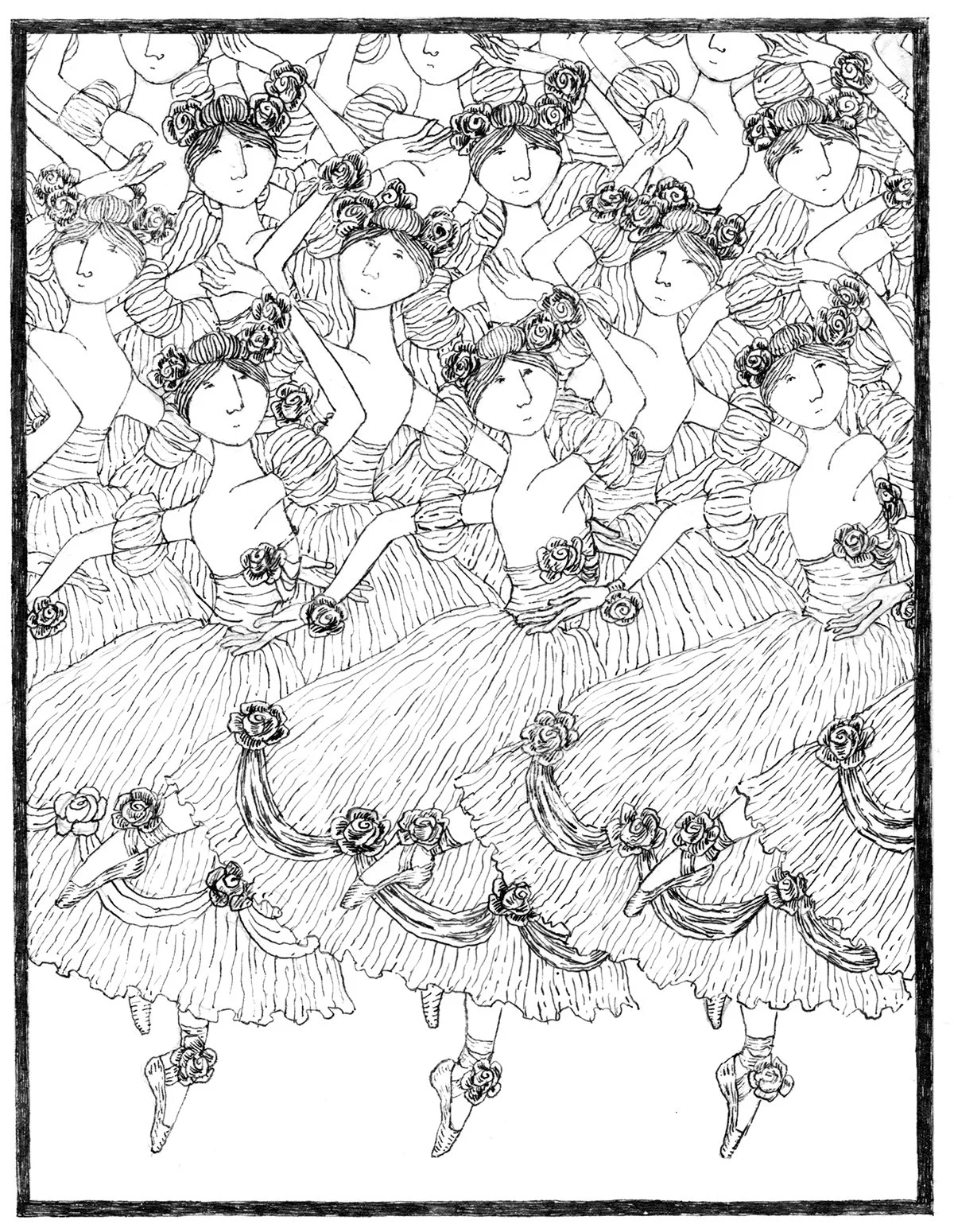

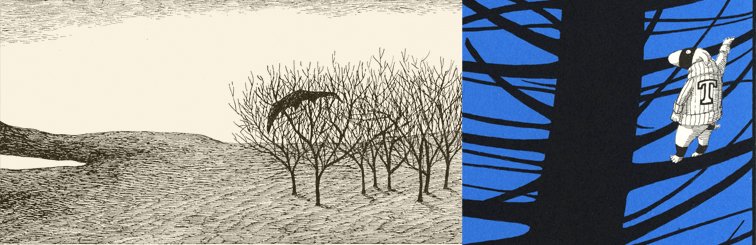

While Balanchine’s phrase Doing the Steps is open to interpretation, it generally speaks of the building blocks—the established, the well-worn (and even worn-out) tropes—used to create something utterly new and vital. Balanchine utilized his decades of dance and musical training, just as Gorey mined a lifetime’s saturation of Children’s Literature, Nonsense, penny dreadfuls, Surrealism, silent film, and Agatha Christie. For both artists, the nuanced effects achieved in their respective works far surpassed the sum of their borrowed parts. Mirroring Balanchine’s storyless stories, movement permeates much of Gorey’s work. Captured in frozen vignettes, in negative and positive space, the cadence of a turning page—even in patterned strokes of a nib across paper—Gorey evokes movement and tension.

While works in Doing the Steps do not depict specific ballets, they certainly mimic Balanchine’s exploration of form, density, and ambiguity. Dance critic Arlene Croce’s 1975 comment about Balanchine still applies to Gorey’s lifetime of works as well: “Since it is an imaginative world we enter when we go to the ballet, the fact that we are unable to formulate their meanings only strengthens their power to affect us.”

Doing the Steps exhibited at the Edward Gorey House

April 7th through December 31st 2022.